Os Cestlavie / Rose Slavy, Untitled II (from the « In-formes » series )

2025, 89 x 116 cm + 7,5 x 9,5cm

Acrylic and watercolor pencil on canvas, diptych

Peinture acrylique et crayon aquarelle sur toile, dyptique

« You are that which is most distant from you, that which is most formless. »

Jacques LACAN

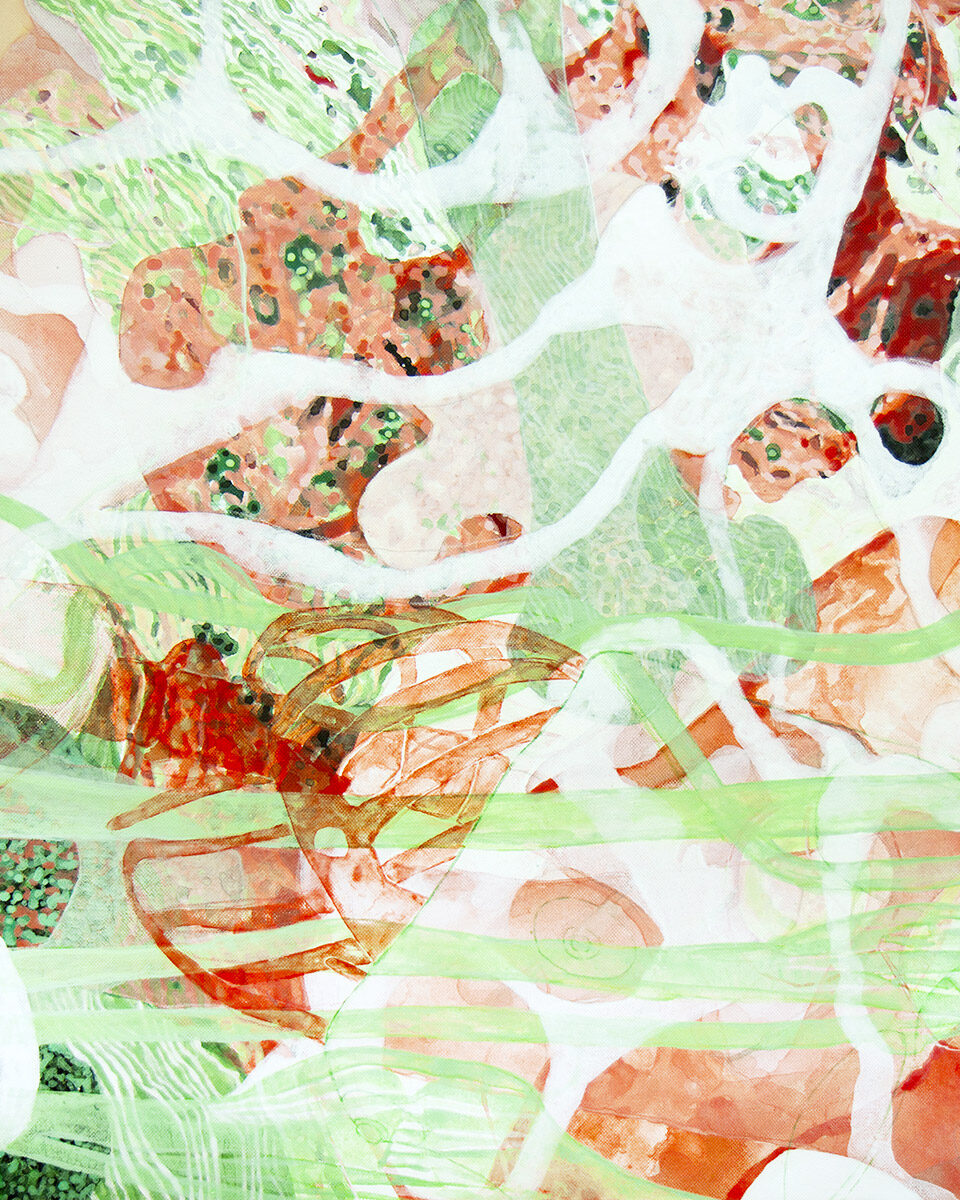

The series of diptych paintings « Form-less-ness » could have been titled « Stain work », as in French these two worlds ressemble (tâche and tache). Or « Eel Soup » which was apparently Aby Warburg’s favorite dish, whose research focused on the phenomenon of interweaving things. Or « Por(r)us », since « porus » is the stone capable, according to Pliny the Elder, of eternally preserving bodies, and « Porrus » — the hamlet in french Ariège where a colored rain of lichens stains our family tombs. In the end, the title « Form-less-ness » was chosen because in the accidental movement generated by forms, in their altercations and alterations, through the apparent chaos, forms irrevocably form themselves, transform, deform, and reform. Infinitely.

The « Form-less-ness » series highlights decidedly cruel, transgressive, Bataillean resemblances. They can be seen as « torn » self-portraits, where one accepts to look at oneself in full truth, that is, from within, in flesh and bone. Recognizing oneself in formlessness, lowering, declassing, calcining, crystallizing, fossilizing oneself can lead to a kind of changing eternity.

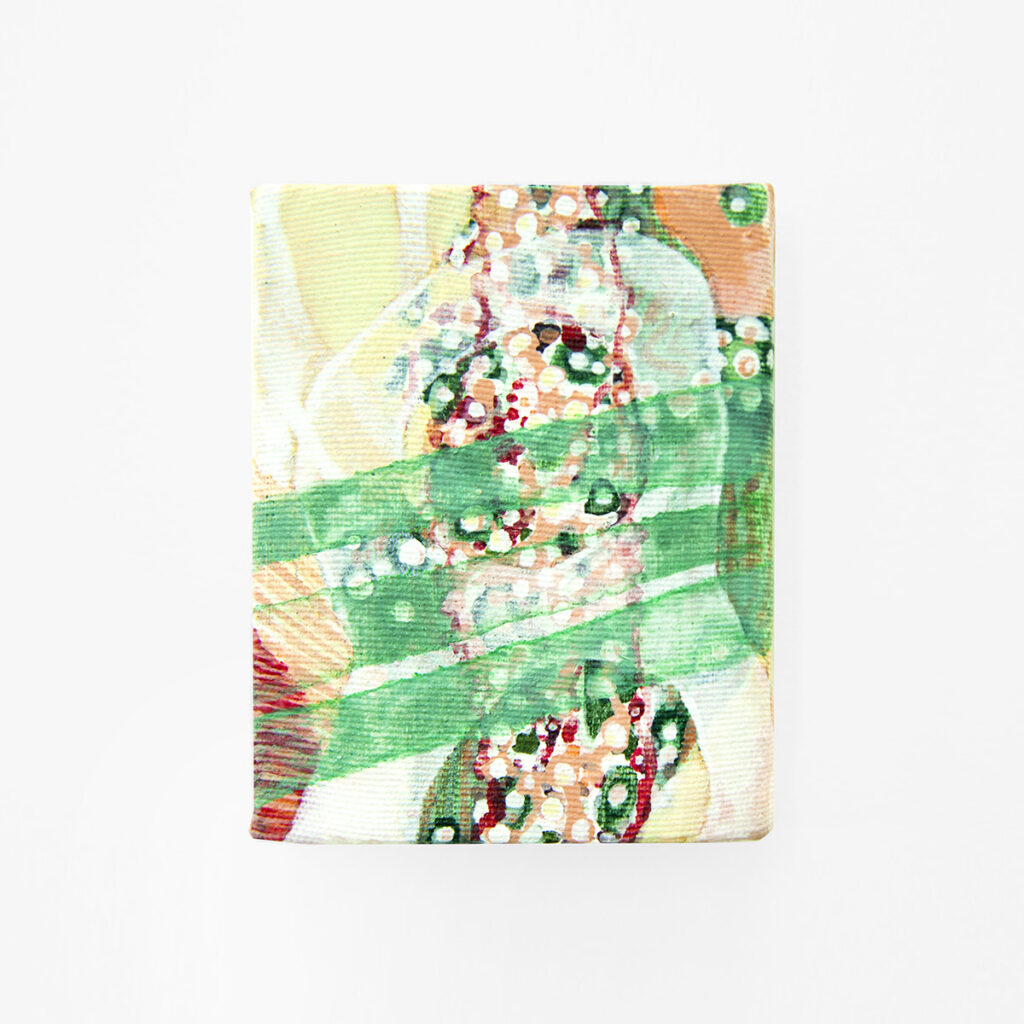

The « Form-less-ness » series unfolds in diptychs because there is always a double within us, the first of the infinite series of our possible variations, the one that is, as Borges says, « the truest » or, according to Didi-Huberman, whose strong resemblance makes the double paradoxically dissimilar. It does not matter if the Other is less visible, smaller, hidden. It watches over the visible part, regards it, questions it. It is the logical continuation that saves us from the solitude of the One.

Dissimilarity is everywhere. Its unsettling presence and uncanny beauty are royal paths to mystery, toward what is not comprehensible, not depictable, thinkable, imaginable, or graspable. The ruin of the body and its anthropomorphic aspect allows this transmutation into raw material seized by vital swarming, which fossilizes into reinvented lives, petrifies into veined marbles, unfolds into incarnate coral cultures. Thus we discover the mineral and vegetal depths of the human.

The aspect being « liquefied » in the series, the formlessness proceeds like a liquid. Stains of flowing pigments, half-splashes, half-spits, half-sprays, obey the laws of fluid dynamics: condensation, runoff, pouring, drainage, mixing, fusion, but also weeping, coagulation, oozing, lactation, ejaculation, urination. Colors flow, drip, overflow, stagnate. As if they were humors of human nature spilled on the surface in colorful catharsis. As Georges Didi-Huberman reports (whose works largely inspired what is being written here), according to medieval theology, the pure visuality of variegated marbles activates « a conversion of the gaze ».

What looks back at us from these canvases, among various anatomical forms, are hilarious masks of pelvic bones, with the terrible beauty of their functional lines. Light as butterflies, they flit through fleshy meadows where forms and « forme-less-ness » grow together in mille-feuille layers of the living. Their joyful metamorphoses transform the viewer, for, according to Bataille, « the dislocation of forms leads to the dislocation of thought ».

Above the bones of our ancestors lie gravestones invaded by lichens, those true flowers of tombs, those little « multi-partner » miracles, those living splashes that honor the founding event of life as we know it, when the first eukaryotic cells formed from the symbiotic union of two distinct organisms. Here is the multiple that passes through the monstrous phase to manifest as the One. Forms and formlessness, like humans, engender, come and go, live and die, are reborn and haunt cemeteries. This cycle suggests that there is no opposition between matter, form, and spirit — all unstable, all impure, but traversed by the eternal principle that moves them in perpetual motion. The formless at work.

« Tu es ceci, qui est le plus loin de toi, ceci qui est le plus informe. »

Jacques LACAN

La série des peintures diptyques « In-formes » aurait pu avoir pour titre « Ta(^)ches », car il s’agit des goutes du pigment liquide qui travaillent les formes en elles-mêmes. Sinon, « La soupe d’anguilles », le plat préféré d’Aby Warburg, dont les recherches visaient le phénomène d’entrelacement des choses. Ou bien « Por(r)us », car « porus » est cette pierre capable, selon Pline l’Ancien, de conserver éternellement les corps, et « Porrus » – le hameau en Ariège où une pluie colorée de lichens macule les tombeaux familiaux. Mais si le titre « In-formes » a été retenu, c’est parce que dans ce mouvement accidentel engendré par les formes, dans leurs altercations et altérations, à travers le « cha-os » apparent, les formes, irrévocablement, se forment, se transforment, se déforment et se reforment. À l’infini.

Les « In-formes » pointent les ressemblances décidément cruelles, transgressives, bataillennes. Elles sont ces autoportraits « déchirés », où l’on accepte de se regarder en toute vérité, c’est-à-dire au-dedans, depuis l’intérieur, en chair et en os. On s’y reconnaît, dans cet informe en devenir, on se rabaisse, on se déclasse, on se calcine, cristallise, fossilise, et par là, on retrouve une sorte d’éternité changeante.

La série « In-formes » se décline en diptyques, car il y a toujours un double en nous, le premier de l’infinie série de nos déclinaisons possibles, celui qui est, comme dit Borges, « le plus vrai » ou, selon Didi-Huberman, dont « la ressemblance si forte le rend dissemblable ». Peu importe si l’Autre est moins visible, plus petit, caché. Il veille sur la partie visible, la regarde, l’interroge. Il est cette suite logique qui nous sauve de la solitude de l’Un.

La dissemblance est partout. Son inquiétante présence et son étrange beauté sont les voies royales du mystère, vers ce qui n’est pas compréhensible, pas figurable, pensable, imaginable ni saisissable. La ruine du corps et de son aspect anthropomorphique permet cette transmutation en matière première saisie d’un grouillement vital, qui se fossilise en vies réinventées, se pétrifie en marbres veinés, se déploie en coralicultures incarnates. Ainsi découvre-t-on les profondeurs minérales et végétales de l’humain.

L’aspect étant « liquéfié », dans la série, l’informe procède comme liquide. Des taches de pigments coulants, mi-éclaboussures, mi-crachats, mi-gerbes, obéissent aux lois de la dynamique des fluides : condensation, ruissellement, déversement, drainage, mélange, fusion, mais aussi larmoiement, coagulation, suintement, lactation, éjaculation, miction. Les couleurs s’écoulent, dégoulinent, débordent, stagnent. Comme si elles pouvaient être des humeurs de la nature humaine répandues sur la surface en catharsis colorée. Georges Didi-Huberman (dont les travaux ont inspiré ce qui s’écrit ici) rappelait que selon la théologie médiévale, la pure visualité des marbres bigarrés activerait « une conversion du regard ».

Ce qui nous regarde depuis ces toiles, parmi diverses formes anatomiques, ce sont des masques hilarants d’os de bassins, avec la terrible beauté de leurs lignes fonctionnelles. Légères comme des papillons, elles butinent dans des prairies charnelles où les formes et les « in-formes » croissent mutuellement en mille-feuilles du vivant. Leurs joyeuses métamorphoses transforment le regardeur, car, selon Bataille, « la dislocation des formes entraîne celle de la pensée ».

Au-dessus des ossements de nos pères gisent des pierres envahies par les lichens, ces vraies fleurs de tombeaux, ces petits miracles « multipartenaires », ces éclaboussures vivantes qui honorent l’événement fondateur de la vie que nous connaissons, quand les premières cellules eucaryotes se sont formées à partir de l’union symbiotique de deux organismes distincts. Voici le multiple qui traverse la phase du monstrueux pour se manifester comme l’Un. Les formes et les in-formes, tout comme les humains, s’engendrent, viennent et vont, vivent et meurent, renaissent et hantent les cimetières. Ce cycle incite à penser qu’il n’y a pas d’opposition entre la matière, la forme et l’esprit, tous instables, tous impurs, mais traversés par l’éternel principe qui les meut en perpétuel mouvement. Informe à l’œuvre.